Parmoor |

Parmoor and the Cripps family | ||||

|

Introduction Parmoor and the D'Oyley family Parmoor and the Cripps family The 1954 notes on Parmoor The 1946 sale |

[ The following piece was written by (Alfred Henry) Seddon Cripps, 2nd Baron Parmoor (1882–1977)

in 1970 at the request of the Frieth Village Society and was included in

the folder "A History of Frieth" compiled by Joan Barksfield ]

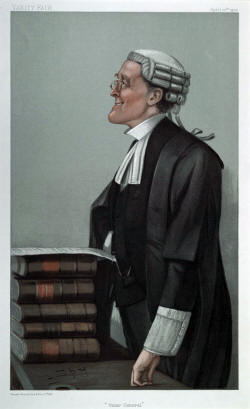

"When time shall steal our years away And steal our pleasures too, The mem'ry of the past will stay And half our joys renew". Thomas Moore. Our grandfather, Henry William Cripps, born in 1815, came to Parmoor in 1860 with his wife and family. He was the eldest son of the Revd. Henry Cripps, vicar of Preston near Cirencester, whose father, Joseph, was Member for Cirencester and later Father of the House of Commons. He was educated at Winchester and New College, Oxford, being head of the school and Prefect of Hall and a Scholar at New College where he later became a Fellow, retaining his Fellowship until he married in 1845. He was President of the Oxford Union Society in 1837. [ See a portrait of HW Cripps here: https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/henry-william-cripps-esq-18151899-qc-jp-26998 ] His wife, Julia, was the eldest daughter of Charles Lawrence of the Querns, Cirencester. They were first cousins and had known each other since childhood. He was called to the Bar and became a Queen's Counsel in 1866, his chief work being in the Parliamentary Committee Rooms and on Circuit. He was, by nature, a farmer, devoted to sport and all forms of country life, and was never happier than when talking to his men or to the village children, for whom he always carried a bag of sweets in his pocket which he scattered for them to pick up, usually from above a branch so that they wondered whether he was a wizard, or whether the sweets had fallen, like manna, from heaven. He later was appointed Recorder of Lichfield and Chancellor of the diocese of Oxford; and was also unanimously elected Chairman of the first Buck County Council and of the Bucks Quarter Sessions. Our grandmother, Julia, was a truly devoted wife and bore him a family of nine children. She was a great disciplinarian and a devoutly religious woman; family prayers, as in many families similarly situated, were said once and often twice daily. Three of their daughters married clergymen, one of whom, Herbert Stanton, became Rector of Hambleden, whilst the two others were curates at Frieth. Our grandparents settled down in London so that he could be near his work, and in 1851 they took a country house at West Ilsley on the Berkshire Downs. Our father, Charles Alfred Cripps, the third son, was born there in 1852. Thence, in 1854, they moved to Ipsden House near Wallingford, where they stayed until they purchased Parmoor in 1860. The first mention of Parmoor appears in our grandfather's diary in connection with a visit there on 7th August, 1860 - "In the evening went to Marlow with my wife. No fly could take us to Parmoor that night from Marlow Road Station (later Bourne End Station), so we slept at The Crown in Marlow, and were disturbed all night by a drunken row. Parmoor seemed to be quite an out of the way, unknown, place in the Marlow neighbourhood, and we did not much like the idea of it. The following week we went to Henley to see Parmoor from that side slept at The Red Lion, and were more pleased with it. and finally took it, farm and all". The property had belonged to the Doyleys, who had been large landowners in the district, and then consisted of rather less than 400 acres. The house was in two distinct parts. An old farmhouse on an oak frame filled with rubble, confronting the farmyard, contained the nursery and offices; the rubble was made up of mortar and small twigs with thin bark, said to denote a very old method of construction. The only relics that still exist of this part are the oak beams in the kitchen and the oak used for the banisters and the newels on the hall staircase and for some of the bookcases in the library; this oak was very hard to work and obviously of a great age. The front of the house had been added later and our grandfather erected a new kitchen and servants' hall, with bedrooms over at the back of this portion, and later, the present drawing room and bedroom wing. Later still our parents entirely remodelled the whole interior of the house which our father had purchased when our grandparents retired to Beechwood, near Marlow, in 1884. Mr. Waller, a well known architect, who practised in Gloucester, carried out the work, designing a new East Wing for the nurseries and servants' quarters, and a new entrance and approach in place of the conservatory which, in old days, had to be passed through by visitors before reaching the front door. In the interior design and decoration our mother took a great interest, drawing out many sketches which, in several cases, were incorporated in the new work. Our father made a further addition in 1900 when the large panelled room was added on the west side, with bedrooms over. It is now used as a chapel by the nuns, who purchased the house after our father's death. Before giving any description of our life there, it may be enquired as to why the property was named Parmoor. I recollect that we first thought that it was probably a corruption of some family name - perhaps Par, or Palmer, with a 'moor' attachment; but we were enlightened by an odd coincidence which may be worth mentioning. It so happened that I had gone on a visit to Uppsala in Sweden at the invitation of their Archbishop, who was a friend of my father's and a frequent visitor to Parmoor. My object was to study Swedish methods of farming and I happened to arrive there on the five hundredth anniversary of the University of Uppsala, where most of the ruling classes in Sweden had been educated. There was a large banquet in the evening, to which the Archbishop took me as his guest, and I sat between Herr Undine (their representative at the League of Nations) and a University Professor whose name I did not catch. In the course of conversation the Professor asked where I lived in England and what was the name of the house. I told him, and added that the exact position was not easy to describe to a foreigner. He then asked me if I knew why the house was called Parmoor, I told him that we were not sure but had some rather hazy ideas. He said, "I will tell you: it is called Parmoor because there was a pear orchard by a mere, or pond, there, and Pargrove which is close-by was named for the same reason". I nearly collapsed. To think that anyone living such a distance overseas knew much more than I did of my own home and district made me feel very small, and I wondered if any Oxford professor, living close-by, could have given such a sure reply. However the mystery was somewhat cleared up when the Archbishop told me the next morning that the Professor was the greatest expert on place names in Sweden and probably in the world. I have since seen that the same derivation is suggested in a book called "On Chiltern Slopes", a delightful story of Hambleden parish written by my uncle and godfather, Herbert Stanton, who was Rector there from 1896 -1934, but which I believe is now out of print. The origin of the Cripps family goes far back. It is thought as far as St. Crispin's Day, and a certain Milo de Crispe is believed to have come over from Normandy with William the Conqueror. The first mention (in Burke's Peerage) is of one William Crispe, in 1207, whose sire lived at Stanlake in Oxfordshire Thence the family is traced as moving to Copcot near Thame in the same county in about 1300. It is believed that a farming family of our name for long existed in that district. The pedigree shows that our family moved to Cirencester in the sixteenth century, where they have remained, their descendants still owning considerable properties in those parts. Our branch, as previously mentioned, came to Parmoor in 1860. Our father, Charles Alfred, later took over Goddards and Shogmoor farms and, later still, the Moor, Beacon and Cutlers farms, with the adjacent woodlands, from our grandfather. These, with Flint Hall and Luxters farms, which he purchased, with his Cadmore properties must have increased the total acreage of the estate from less than 400 acres to a little short of 4,000 acres. He at first farmed the land adjacent to the house and later included Shogmoor, Flint Hall and Luxters in the Home Farm which he farmed with the assistance of his bailiff, Mr. Thomas Jess, who first came as gardener and lived with his wife in the cottage on the opposite side of the drive. He came from the Earl of Stairs' garden in Scotland, where he had found his wife who worked at the castle. He stayed with us as farm bailiff for the rest of his life. They had two children, Peggy and Tom, the former dying early in life. Tom followed his father as sub-agent for some time after I had taken over the management of the estate. Jess was a faithful friend; Mrs. Jess an admirable and amiable soul who had been well and strictly brought up in the true Scottish way of life, not often leaving her cottage and content in spending her days loyally attending her husband and family, and anxious at all times to give assistance and prudent advice to those in need. She was especially kind to us children and we constantly visited her at tea-time when we quickly devoured her delicious home-made scones and cakes, which she had specially cooked for us. She always used a girdle , which one rarely finds in a kitchen now-a-days south of the Border. I remember once asking for one in a Store - the hardware department had never heard of it and referred me to the 'lingerie' assistant! Our mother was one of the nine daughters of Richard Potter, who was descended from an industrial family living at Tadcaster in Lancashire, which, in early days, had become involved in the industrial revolution which has raged since the end of last century, and unfortunately is as yet by no means settled. His wife was Laurencina Heyworth, whose father was for many years Member for Derby. Two of the nine daughters married into the Cripps family; William Harrison, later a distinguished surgeon, married Blanche Potter, whilst our father, Alfred, married her sister Theresa. Richard Potter lived at Standish, near Gloucester, where he was a partner in the firm of timber merchants, Price & Potter, who supplied the huts both for the French and English in the Crimean War. There was a story of him 'posting' across France to see the king himself about the contract. He was also chairman of the Great Western Railway Company and of the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada, also, I believe, of the Hudson Bay Company. Another of the nine sisters was Beatrice who later became Mrs. Sidney Webb. When she first brought her husband to stay at Parmoor after their marriage I recollect my father who in those days, was a staunch Tory, turning to me as they drove away, with a half wink and saying: "Have you counted the spoons?" It is amusing to know that later they became great allies, in fact, both served in the first Labour Cabinet, one as Lord President of the Council and the other as Colonial Secretary. Our parents were married from Rusland Hall in the Lake District in 1881 and I arrived in the world in August 1882, the first of five children. Our mother was very ill after my arrival at Standish where she was staying for the event. The house, perhaps appropriately, is now a maternity home run by the Gloucester County Council and I hope I gave it a good start! I was fostered for some time by Jane Burridge, the wife of a woodman, who often acted as keeper in early days. After leaving Skirmett they went to live at Bagmoor, when the farm there was incorporated with the Home Farm; his nickname was "Booby" which he hardly deserved, as anyone out shooting could at once see that he was dealing with a master craftsman when it came to smoking out his favourite ferret, Jacob! Perhaps the effect was largely due to the powerful smell of the village shag which, as far as I recollect - and I often tried it - was very pungent.

I forget in what year the annual flower show started but I fancy it was held in Frieth before coming to Parmoor. Most of the villagers had gardens and showed either flowers or fruit, whilst others brought cakes, needlework or lace, which was made then on pillows by the villagers both in North and South Bucks. One could often see old ladies sitting outside their cottage doors in summer, under sun-bonnets, weighed down by a huge bolster on which there were hundreds of pins through which the cotton was delicately wound to form the pattern of lace. When machine-made lace came in, the trade dwindled, as this was much cheaper and more accurate. Also making lace was said to be very trying for the eyes, and, for this reason, as well as for it being a long and tedious process, the rising generation did not readily take to it, and it soon died out, though I believe a small amount is still handmade in North Bucks, and probably around Honiton in Devonshire which was always one of the chief centres of the industry. After the exhibits had been judged by some discerning gardener, usually from one of the large houses in the district, the show opened about 2 p.m. and the villagers started arriving, many to see what fortune had brought them in the way of prizes. Sports usually then took place - a mixed variety- three-legged, egg and spoon and short distance races for boys, their sisters and their elders. Tea was later served in large tents erected in the field. I think we provided much of the fare but others probably contributed, and certainly took their full share by arranging the tables and serving tea from out of the large urns as people arrived. There was no charge, and at first no tickets, but these later became necessary as many non-villagers turned up from a distance owing to increased ease of transport and once or twice the large supply of food threatened to fail. After tea, the school children usually danced round the Maypole and then the prizes won at the sports were presented. The Lane End Band played during the afternoon and there was dance music later in the evening. The floor was usually the dry lawn so that if rain came, as often happened, the day finished and they wended their way home with their exhibits and prizes if they had been lucky. My father and mother (as long as she was alive) spent their time walking about and chatting to everyone, most of whom they knew as old friends and valued neighbours. We children had to make ourselves as useful as possible and helped with the sports and the tea and saw that the other children were kept out of mischief and enjoyed themselves. It took the garden some time to recover, though all, in those days, seemed very well behaved and we rarely had any cause for complaint. I remember that if the dancing appeared to go on for too long in the shades of evening, or the elders seemed unduly tired, Jess, the bailiff, would try to comfort my father by telling him that he thought there would soon be a helpful shower which should excite a homeward move of the company! Another annual event which deserves mention was the Harvest Home for those employed on the estate. It was held after the harvest had been gathered in September and consisted of a high-tea given in the large coach-house to all the men employed by us, and their wives. The same tables and trestles were used as for the tea at the flower show and I think that, judging by their appetites, many of our welcome visitors must have starved for days in advance. It took quite a heavy toll of our flocks and herds to contribute to the feast, to say nothing of the fowls and larger poultry; whilst our cook made plum puddings and various other sweets. After the tables had been cleared, clay pipes and tobacco were handed round for those who smoked, and songs of all description were sung. Our chief favourite was sung by Jessie Rylands, one of the carters, it ended up "There were three rats came ratling back with thirty bright guineas in th' empty sack, with a bunch of green holly and ivy; and he winnowed it out with the tail of his shirt and a bunch of green holly and ivy". There were, of course, the lugubrious love-songs drolled out in suitably painful tunes which we children did not appreciate, but they were always popular with the adolescent and the middle-aged; had the Beatles suddenly arrived, I think a general retreat would have been quickly sounded and the coach-house speedily emptied with a rush for the protection of their village homes. My father made a short speech of welcome during the evening which finished about 10 p.m. There were also Hunt Breakfasts at Parmoor when the Old Berkeley Hounds occasionally met there, or the Hambleden Vale Harriers, which my grandfather had kept at Goddards and which I later resuscitated and kept at Shogmoor. He had Snaith as kennel huntsman and I had Fred Napper who later went to Lord Leconfield at Petworth. There had always been good shooting at Parmoor as the woods and plantations were on the whole well placed and provided sunny banks for game, and the mixed farming in those days chiefly consisted of roots and corn which harboured partridges and hares. My brother, Colonel Fred Cripps, was the great exponent of the art as far as our family was concerned, though Leonard was also a good shot. I remember once hearing that a London gun-maker thought that my brother Fred let off more cartridges in the year than anyone in England, but I fear he has now to pay the penalty by having become rather deaf as the result. Besides the hounds, we always had a host of dogs of all sorts at Parmoor and a stud of riding and carriage horses, all of us being fond of riding, whilst I was particularly fond of driving tandem along the country lanes, now an impossible ad venture! My father for long rode his hack round the farm and often to Luxters and to Cadmore End to see his tenants there, and the brick kiln (which the admirable Mr. Rose supervised for him) and later, of course, round the Moor Estate. It was very good riding country as, apart from our own land and woods, there are numerous commons and bridle ways, and I had the permission and even the welcome of the farmers to go about almost anywhere as long as the gates were shut and followers of the hunt did not ride over the corn or root crops; and of course the large Chiltern woodlands are ideal for summer hacking. I must mention the woods at Parmoor. It has often been said that Chiltern landowners made on their woods what they lost on their farms, and there was a good deal of truth in this adage. In those days farms were usually not large enough to justify much capital outlay and had survived chiefly as small family farms, carved out of what must have been once all forest. There were of course some notable exceptions in the valley and at Chisbridge, a first class farm, run for many years by a knowledgeable family, the Keenes, who were well known in kindred enterprises. There were no combine and quick-drying harvesters in those days and much of the reaping had to be done by hand, and the flail used if a threshing machine could not reach the farm which was sometimes the case. Many of the village women went gleaning and many good handfuls were picked up which the rakes had not cleared before the wagons arrived to cart the sheaves home. Our carters, I was always told, though I confess I never got out to see, fed their horses about 5.00 a.m. and were in the fields ready for work as soon as light came. They had their cold tea and cheese or whatever they brought with them at about 8.30 a.m. and came back to the stable at about 11.00 o'clock so as to escape the heat of the day. They then fed their horses and went back to their own meal, returning to groom their animals later on. Then they cleaned up their 'tack' and gave their horses their evening meal, returning to their own high tea, and going to bed early so as to be up at the right time the next morning. There was then only candlelight in the cottages, with an occasional lamp, so there was not much inducement to read or write after dark, and they would often proceed to the 'local' at Frieth, or 'The Pheasants', where they could discuss with their friends all parochial affairs, not excluding our boyish adventures. We had many visitors at Parmoor in those days and we brought back our friends from school, and went to parties given by other families living in the district. As far as we were concerned, the early days of this century after the South African War and the death of Queen Victoria, were days of quiet contentment and leisure; and I remember that we were assured by all that it was extremely unlikely that there would ever be another war! Although our mother had died in 1893, after a very sudden illness, we were particularly fortunate in having, in addition to our sister, Ruth, whom we all worshipped, some excellent attendants and servants, many of whom stayed at Parmoor for long periods of time. In addition to one, Margaret, who was originally nursery-maid, and stopped with us until she married one of the footmen, we had Mary Marshall, affectionately known as "Mazelle", who came from Alsace to teach us French, and stayed with us for about 30 years, when she went to help my brother, Stafford, with his household in, Gloucestershire for another long period before retiring to Cornwall with her niece, where she died at the age of 102. It always seemed a source of wonder to many that anyone could have put up with us boys for so long! In 1914 the golden age at Parmoor came to an end, as elsewhere, when war was declared. I remember that our uncle. Lord Courtney of Penwith, a staunch and shrewd Cornishman, who had been Deputy Speaker of the House of Commons, where he was Member for Bodmin, said at tea on that day (August 4th) that England would never be the same again. It certainly never has been!

After the war, in which my brothers Fred (who commanded the Bucks Yeomanry) and Leonard (who was in Sir Winston Churchill's old regiment, the 4th Hussars) were both severely wounded, we returned from our various duties; but Parmoor, though it had been fortunate and escaped any bombing or damage, never seemed quite the same again. The atmosphere had changed from that of a quiet family home to a semi political house, as my father had, with Lords Haldane and Chelmsford, agreed to assist the first Labour Government in the House of Lords, where, naturally, it had hardly any representatives. He became Lord President of the Council, whilst my brother Stafford soon started what was to be a speedy political climb and became Solicitor-General. In 1919 my father married Marian Ellis, a Quaker, who had assisted the 'Save the Children Fund' and was interested in the 'League of Nations', my father being in the absence of the Prime Minister, our Country's chief representative at Geneva. Many political and foreign visitors, including Herr Streseman and Herr Luther came to Parmoor, together with friends whom we had met in various ways during war years. My sister, Ruth, was married, and so were my brothers, Fred, Leonard and Stafford, whilst I became Bursar of Queen's College, Oxford, which enabled me also to combine the management, with the assistance of Tom Jess Jnr. and later Mr. Sherwood, of the Parmoor Estate. There were also held, during the post war period, various conferences and religious retreats at Parmoor, often attended by the Bishop and other leaders of Church work, in which our father and step-mother and my brother Stafford were all greatly interested. At the end of an uneasy period of peace, Hitler came to the fore, and again, as all know, gradually obtained control of Europe, after temporarily settling with Russia, leaving England and France to bear the brunt of his attack. War, though staved off for a time by Mr. Neville Chamberlain, became inevitable and the challenge had to be accepted. Early in the war, in 1941, my father died and Parmoor had to be let until such time as its future could be decided. We found, as you will know, a curious tenant, King Zog of Albania, who occupied it with his beautiful Queen during the second war period. Many stories were told of his 'reign' there. I remember one about the picture of our Grandfather and Grandmother painted for their Golden Wedding. King Zog was reported as saying to a friend in London that we had a very fine picture at Parmoor of Queen Victoria talking to Mr. Gladstone! Our Grandfather, a real old Tory, would not have been much flattered! After King Zog left, with his large entourage, early one morning for Alexandria where King Farouk of Egypt had offered him hospitality, the fate of Parmoor had to be decided. It had obviously become too large and costly for the sole occupation of a bachelor, and in any case, I had to live at Oxford. The difficulties of staff, inside and outside, had become great and seemed likely to get worse, so the only alternative appeared to be to sell or let on a long lease. I am glad we decided to sell, though it was a painful decision, as it never would have been possible for any of the family to live there. We were fortunate in finding purchasers for the house whom we could welcome, and were happy to know that a religious community would be able to appreciate its restful peace which we had so long enjoyed. I was rather alarmed lest some speculating adventurer might swoop down and attempt to buy it, who might have had little regard for his neighbours in the village and the surrounding countryside. This brings to an end a short, and I fear, somewhat inadequate glimpse of Parmoor as we knew it; more recent history is better known by those who have lived nearby. We can only hope that, though conditions have entirely changed, it may not have lost all its pristine charm and beauty. Before I close, I must say how grateful we were to the villagers at Frieth for all their many kindnesses and forbearance whilst we spent our younger days amongst them; we certainly learnt more from them than they can have ever learnt from us, and we still much value our connection with the village and district by retaining several hundred acres of property - at the Moor, Beacon, and the woods there (including also Mousall's and Moor End Woods), a corner of the Churchyard, where we hope eventually to rest, an interest in the Village Hall, erected in memory of our mother, and the name which closely links the Cripps' family to the village and which I now have the honour to bear, PARMOOR - (of FRIETH). I should particularly like to congratulate the Village on winning the Cup (this year) for the best-kept Buckinghamshire village; I hope it may remain so. I wish also to record my indebtedness to my sister (Lady Egerton) for kindly checking the account, especially as regards names and dates. P. THE ARMS A print of the Arms can be seen in Burke's and in Debrett's Peerages. The heraldic description is:- Shield - Chequy ermines and argent, on a chevron vert five horse-shoes or. Supporters - On either side a sea-horse proper, supporting a pennon ermines charged with a swan rousant argent beaked and legged gules ducally gorged and lined or. Crest - An ostrich's head couped argent gorged with a coronet of fleur-de-lyes and holding in the beak a horse-shoe or. Motto - "Fronti nulla fides". Notes: Tinctures: Ermines - black with white spots. Argent - silver. Vert - green. Or - gold. Gules - red. The Shield - The tincture was differentiated from the usual Cripps shield (or) on conferment of the peerage. The Supporters were chosen as the Potter family crest was a sea-horse; the swan on the pennons is the emblem of the county of Buckingham, the first baron having been chairman of quarter-sessions, a county councillor, and member of parliament for the Wycombe division. The Motto - "No faith in appearance" Haec olim, forsans, vobis meminisse juvabit, Sic sperat scriptor, laudator temporis acti. August 27, 1970 P. (aetat, 88). |